CHRISTMAS is the most fattening time of the year. There are claims that the average Westerner will consume 6,000 calories on December 25th, well over twice the recommended daily intake for men and more than that for women. He or she could put on nearly two kilos in the last week of the year. Short winter days and too much slouching in front of the television accounts for some of that. But the main cause of festive obesity may well be sugar, an essential ingredient in Christmas pudding, brandy butter, chocolate, marzipan, mince pies and alcohol.

The author sets out to prove that because of its unique metabolic, physiological and hormonal effects, sugar is the new tobacco. It is detrimental to health, yet also defended by powerful lobbies. If, as he contends in one example, the most significant change in diets as populations become Westernised, urbanised and affluent is the amount of sugar consumed, then the conventional wisdom linking fat with chronic disease does not square up. Cultures with diets that contain considerable fat, like the Inuit and the Maasai, experienced obesity, hypertension and coronary disease only when they began to eat profuse amounts of sugar. Likewise, diabetes—virtually unknown in China at the turn of the 20th century, but now endemic in 11.6% of the adult population, 110m in total.“Sugar spoils no dish,” averred a 16th-century German saying. But it certainly spoils and savages people’s health, says Gary Taubes, an American science writer who has focused heavily on the ills of sugar over the past decade and is the co-founder of an initiative to fund research into the underlying causes of obesity. In “The Case Against Sugar” he argues that dietary fat was fingered for decades as the perpetrator of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. Abetted by an industry that funded scientific research linking fat with coronary disease, sugar, the real culprit according to Mr Taubes, was allowed to slip off the hook.

Sugar is intoxicating in the same way that drugs can be, writes Mr Taubes. Was it not Niall Ferguson, a British historian, who once described sugar as the “uppers” of the 18th century? A medieval recipe even suggests sprinkling sugar on oysters. The craving seems to be hard-wired: babies instinctively prefer sugar water to plain.

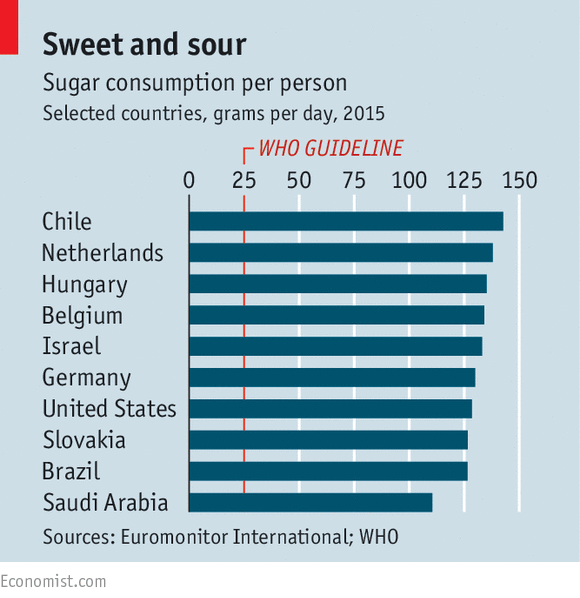

As sugar shifted from being a “precious product” in the 11th century to a cheap staple in the 19th century, the food industry proceeded to binge on it, with unheeded consequences. The biggest consumers today are Chilean (see chart). The Dutch, Hungarians, Belgians and Israelis are not far behind. Saudi Arabians also have a sweet tooth. In only ten countries do people eat fewer than 25 grams of sugar a day.

Sugar lurks in peanut butter, sauces, ketchup, salad dressings, breads and more. Breakfast cereal, originally a wholegrain health food, evolved into “breakfast candy”—sugar-coated flakes and puffs hawked to children by cartoon pitchmen like Tony the Tiger and Sugar Bear. A 340ml (12-ounce) fizzy drink contains about ten teaspoons of sugar. Even cigarettes are laced with it. Bathing tobacco leaves in a sugar solution produces less irritating smoke; it is easier and more pleasant to inhale.

Woe, however, to the scientist incautious enough to challenge the party line exonerating sugar. Mr Taubes tells the story of John Yudkin, a nutritionist at the University of London. In the 1960s, Yudkin proposed that obesity, diabetes and heart disease were linked with sugar consumption. Though he acknowledged that existing research, his own included, was incomplete, he became embroiled in a scientific spitting match with Ancel Keys, a well-known American researcher. Keys, whose work on dietary fat as the prime cause of coronary disease had been supported by the Sugar Association for years, ridiculed Yudkin, calling his evidence a “mountain of nonsense.” The clash—Mr Taubes calls it a “takedown” of Yudkin—is a sad chapter in what Robert Lustig, a paediatric endocrinologist at the University of California, San Francisco, calls “a long and sordid history of dietary professionals in the U.S. who have been paid off by industry”. When Yudkin retired as chair of his department in 1971, the university replaced him with an adherent of the dietary-fat theory.

Because research specific to sugar’s deleterious effects is wanting, the science, Mr Taubes concedes, is not definitive. But it is compelling. The case against sugar is gaining traction. In October the World Health Organisation urged all countries to impose a tax on sugary drinks. Mexico had already done so in 2013. In America cities including Chicago, Philadelphia and San Francisco are following suit. Britain will implement a soft-drink levy in 2018. South Africa and the Philippines have measures under consideration. Perhaps at long last, sugar is getting its just desserts.

No comments:

Post a Comment